The Asian America Through Art Exhibition is a series of projects depicting Asian, Pacific Islander, and Desi American (APIDA) issues through digital and physical art. Rutgers APIDA students and allies in the Asian American Cultural Center’s (AACC) Junior Internship program and the Asian American Identities and Images Living Learning Community have worked throughout the semester to discuss topics like xenophobia, immigration, Islamophobia, cultural and ethnic identity, and colorism and how they impact, influence, and engage APIDA populations today.

Amani Syed

- Amani Syed's artist statemenet

-

The topic I have chosen in American history related to the Asian American experience is Islamophobia being anti-Muslim racism. You may be thinking, “Wait, Amani. Islam isn’t even a race.” Islamophobia is a product of structural racism but is viewed as a form of cultural racism, especially in the United States. I chose this topic because I identify as a South-Asian American Muslim. Therefore, leading this project through the lens of an American Muslim like myself will allow for perspective and emphasis on Islamophobia not only in the APIDA community but also globally.

As mentioned in Abdullah Al-Arian’s article, “Trump issued an executive order barring all refugees and citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States” and referred to this as the “Muslim ban” (Al-Arian). Muslims face discrimination because of their appearances and names, as well as being randomly selected for additional security checks at the airport, coming from personal experience.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The popular perception of Muslims that converts Islam from religion to race is that Muslims are exclusively from Middle Eastern descent. In reality, Islam is a “multiracial and ethnic group,” and “black Muslims rank as the biggest group in America” (Desmond-Harris). Both Muslims and non-Muslims discriminate against black Muslims by assuming that they are converts and not born into the religion. Prominent Muslims likes Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali have helped shape black-identity in Islam. According to Abdul Khabeer in “The Peculiar Case of the Black American Islamophobe,” black and Muslim folks “threaten the [white] nation through their violent behavior, pathologies, and overall ‘bad’ culture” (Khabeer). One can only imagine the difficulties that come with being a black Muslim in 21st Century America. American Muslims, specifically from South Asian descent, nowadays are more focused on upholding an image rather than changing the overall narrative. A majority of Muslim and non-Muslim folks do not know what to do when witnessing Islamophobic harassment, which is surprising because these incidents occur daily. In countries like China and India, Muslims are focused on survival because of the hardships they face. Currently, as we learn to live alongside COVID-19, Chinese and Indian Muslims face even more difficulties than before, as they are being blamed for the spread of the disease because of the large gatherings that occur during prayer in the mosque. Muslims globally have become the scapegoat for those who are cowardly, especially American Muslims. Muslims in America must step up and take the first initiative for breaking stereotypical and racist norms for Muslims all around the world to feel safe. We do not appreciate the freedom and luxuries we have in the United States and forget that Muslims in India and China have to hide their identities when leaving their homes. Taking control of our Muslim identity has become normalized through my generation because we are no longer looking to survive as our parents did; we are looking to live. It is time for American Muslims to own up to the Islamophobic remarks that have been made even before 9/11 and fix the terrorist image sculpted by capitalism for good.

Originally, pre-COVID-19, the original mode of art I had chosen was an acrylic canvas painting. Due to the current conditions, the method of art shifted to digital, graphic art. The art piece consists of a portrait frame of a woman wearing a bright, fuchsia, hijab with “Islamophobia” written on her face in bold lettering. Behind the women read headlines regarding Islamophobia from all over the world. This art form was the only way, in my opinion, to visualize what it means to be an American Muslim in a world of Islamophobic harassment.

- Works Cited

-

Al-Arian, Abdullah. “Islam, Muslims, and the Trump World Order.” Jadaliyya, Jadaliyya, 3 Mar. 2017, www.jadaliyya.com/Details/34067/Islam,-Muslims,-and-the-Trump-World-Order.

Desmond-Harris, Jenée. “Islam Isn’t a Race. But It Still Makes Sense to Think of Islamophobia as Racism.” Vox, Vox, 2 Feb. 2017, www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/2/2/14452388/muslim-ban-immigration-order-islamophobia-racism-muslims-hate.

Khabeer, Abdul. “The Peculiar Case of the Black American Islamophobe.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 5 Oct. 2011, www.huffpost.com/entry/us-islamophobia-_b_917134?guccounter=1.

Banni Anand

-

Banni Anand's artist statement

-

I chose to make a painting because it is what I think I am good at, but I challenged myself to make the subject people since I usually make abstract pieces.

My painting Identity is about the ways I may identify as an Asian American. The three women depicted in the piece show how there isn’t just one look to be Asian American. I chose to use three women to show 2 extremes and 1 neutral. All three of them are intended to be Asian American but in different capacities, where one does not outweigh or invalidate the others.

Looking back at my own experience, I found myself being neutral, and identifying as an Asian American, in claiming both instead of one or the other I felt like a foreigner wherever I went (Hoffman). I didn’t look Asian enough for my Asian peers or American enough for my American peers. I often blamed this on not assimilating to American culture enough, but also not following my family’s traditions and culture enough.

Deriving from my experience as an Asian American, I’ve learned that the two words that make up a part of my identity are more than the sum of its parts, and that being Asian and being American are not mutually exclusive. I feel like double consciousness does play into my experience where I am aware of the Asian and American parts of my identity (Luders-Manuel). It can be hard to see the overlap between the two if there is any, “is it just a mix of the two?”, “is there even an overlap?”, or “is it different from person to person?”

As an Asian American I am very much an experience, and I try to be a good one.

To delve more into the topic of identity as an Asian American, I’ve noticed that being American often equates to being whitewashed, which literally means a thin surface layer of white, but in this case it would mean stripping the original culture to conform with “whiteness”. The inverse, being Asian meant to be from Asian descent and to retain the culture from the land of origin. These two appear to be polar opposites, and often force those who identify as Asian American to pick a side, which is a problem in and of itself, and creates a veil, where one party can look outside of their own realm but the parties outside of the veil cannot look in and recognize what is happening within (Macat). The veil puts cracks in the unity the community should have. The veil also pushes the perpetual foreigner by drawing lines and gatekeeping. I try my best to keep the veil off to be more aware and to embrace my Asian American identity.

There is no “one way” to be Asian American.

- Works Cited

-

Hoffman, Christopher. Perpetual Foreigners: A Reflection on Asian Americans in the American Media, Huffpost, 01 Nov. 2016, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/perpetual-foreigners-a-reflection-on-asian-americans_b_5810b616e4b0f14bd28bd19a

Luders-Manuel, Shannon. Black Panther and Double-Consciousness, JSTOR Daily, 28 Mar. 2018, https://daily.jstor.org/black-panther-and-double-consciousness/

Macat, “An Introduction to W.E.B Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk- Macat Sociology Analysis”, YouTube, uploaded by Macat, 6 Apr. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvE3Ft10h2w

Cindy Wong

-

Cindy Wong's artist statement

-

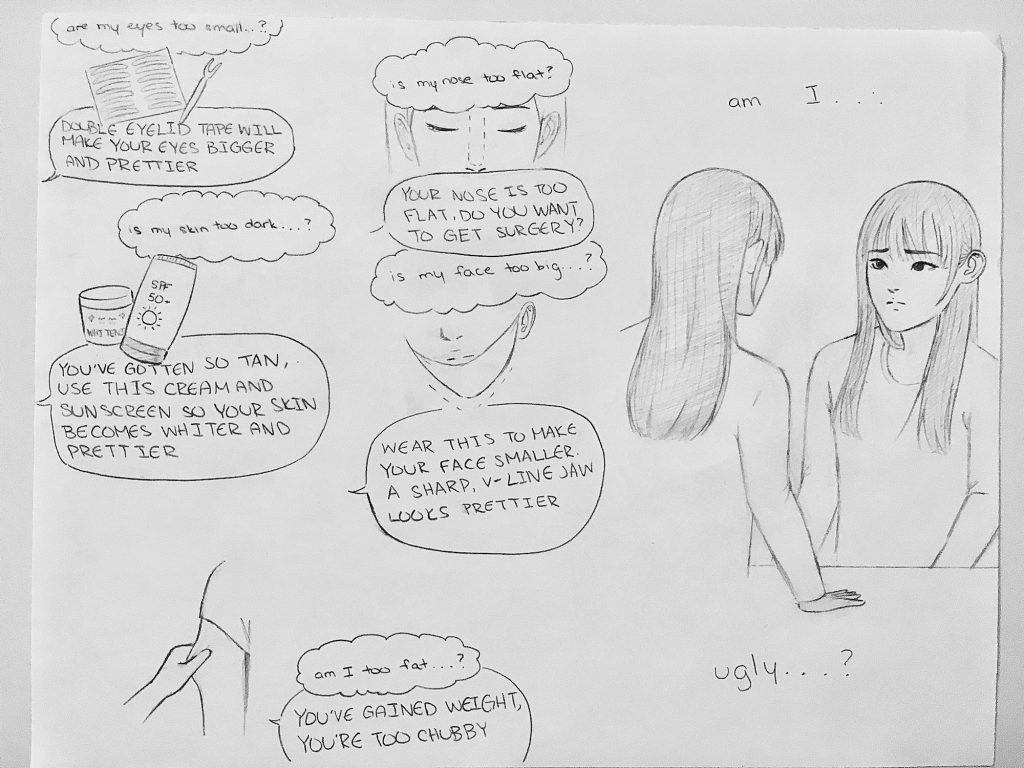

I chose the topic of beauty standards because I think as both an Asian American and a woman, it is something that has been a very prominent thing in my life, as well as in society in general. This issue is important because these pressures and these beauty standards that are pushed upon Asian Americans throughout their childhoods and even their lives has an effect on them and their mental health, as well as their body image. According to Pei-Han Cheng (2014), “the greater body image dissatisfaction people experience, the greater vulnerability they have to adverse psychological outcomes, such as social anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and low self-esteem.”

Cheng also explains that there is a lack in body image studies on women of color and this “ may reflect the assumption that body image issues are the White, upper-middle class, female phenomenon, and the cultural contexts of women of color may provide “protection” against developing body image disturbances” (2014).

However, this is not the case, and many women of color experience these issues as well and “different from White American women, the reason for developing disordered eating behaviors may not only be the societal pressure in pursuing thinness and may be related to their experiences as a racial minority,” which she explains in the example of Asian Americans who are influenced by the American standard of being thin but due to the smaller frames of Asians are often seen as not having any body image issues and a “model minority” because of this, yet also being perceived as a “perpetual foreigner” due to other features like their eyes (Cheng, 2014). While beauty standards do differ around the world, many do seem to revolve around this Western and Caucasian standard of beauty, which can be seen in skincare advertisements in Asia, which are notoriously geared toward skin lightening or skin whitening and Ginwala explains very often feature Caucasian models, with Korea and Japan having 45 and 55 percent respectively (2014). For Asian Americans, there are both beauty standards from their own Asian heritage as well as American beauty standards, and sometimes, and according to an interview done by Dhaya Devayya, “sometimes you feel inadequate because you know you can never fully achieve it” (2007)

I chose drawing a small comic-like drawing because I wanted to try to visually show the experiences of some Asian American women and how they are often influenced by the words of the people around them and society growing up and how it can affect them and their mental health and their own body image.

- Works Cited

-

Cheng, P.H. (2014.) Examining a Sociocultural Model: Racial Identity, Internalization of the Dominant White Beauty Standards, and Body Images among Asian American Women (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University).

Ginwala, A. (2014).“Breaking the Mold: Four Asian American women define beauty, detail identity, and deconstruct stereotypes” (Honors Theses and Capstones, University of New Hampshire).

Devayya, D (2007). “She’s Got the Look”: Cultural Beauty Ideals from the Asian American Woman’s Perspective.

Daniel Au

- Daniel Au's artist statement

-

Throughout over 150 years of American history, Asian Americans have managed to settle and make a living in foreign land that allowed for the creation of cultural communities, for example, chinatowns. Chinese immigrants settled on the east coast of America, most notably Philadelphia, after being driven out from the west in the 1870s from racial violence (Wilson). Once settled, the ethnic community continued to grow for the next century, and eventually turned into the vibrant and cultural Chinatown seen in Philadelphia today. I found this history particularly interesting as I was growing up, my parents would take me to the Chinatown in Philadelphia frequently, and I would remember eating at the various restaurants and shopping at the stores located throughout the town.

Having many vivid memories of the place, I never actually knew the history of how the community came to be, despite the countless times that I have been there. I do believe it is important to learn more about one’s own culture as it is a part of their identity and who they are as a person. As such, researching the topic taught me more of Chinatown’s history and how it was a result of the actions of thousands of Chinese Americans over a century ago. Evidently, not every Chinatown in America came to be because of the same reason; I have chosen to look at the Chinatown in Philadelphia mainly due to the personal significance it had on my childhood and my current experiences as well. The most famous symbol of Chinatown, I believe, would be the friendship arch located on 10th and Arch Street. Completed in 1984, it is considered a symbol of cultural exchange and friendship between Chinatown and its sister city in Tianjin, China (Wilson). As such, I chose it as the main illustration for the project. The art form is a collage mosaic, where the main big picture is itself made of smaller pictures. The left side of the arch is made black and white to symbolize Chinatown’s past and the endless struggle for Chinese Americans to settle and make a living for themselves and future generations. The right side of the arch is colored and represents the Chinatown that is seen in the present -a popular landmark considered by many that shows the influence of the increasing Asian American community and population. The small pictures that make up the arch consists of photos of the Philadelphian Chinatown from both the past and the present, illustrating the direct impact of Chinese immigrants creating a cultural community 150 years ago and how much it has grown since then (Carroll). From the many ethnic murals throughout the town to the cultural Lunar New Year celebrations, Chinatown remains an essential piece of history of the Asian American experience and continues to be a symbol for the ever-growing population and culture.

Echo Hossain

- Echo Hossain's artist statement

-

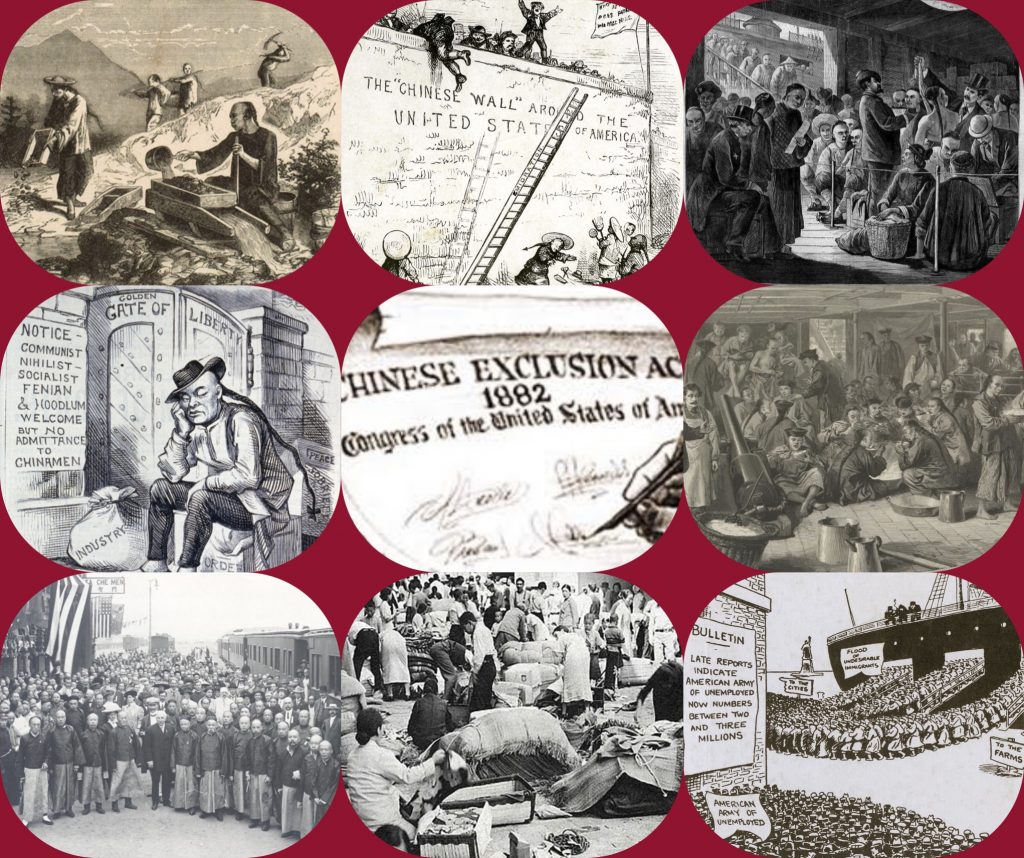

I decided to pick this topic because it reminded me of my friends and family. Before I was born my family always wanted to come to America to start a new life and create a better future for their family. They wanted to live the American dream that they grew up learning about. It was because of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that my parents and many others could make their dream of coming to America a reality. Anti Asian immigration is a really important matter. Let’s look back at the The Chinese Exclusion Act. This act was passed on May 6, 1882 and it was signed by President Chester A. Arthur. This became the first significant law that had restricted immigration in the United States.

The reason this law had come to pass was because many Americans blamed Chinese immigrants for the declining wages that they were facing. Americans also feared that their jobs would be taken from them. This ban continued until 1943, but even after that the process if immigration did not get easier. It was only through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that it had changed drastically. The act was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. I decided to choose this mode of art so that I could portray the entirety of Anti Asian immigration that had occurred during that time. Through these images anyone can see the hardships that the families were going through. People were coming to America for a better life and a brighter future, but they were not able to achieve that. I believe that one image could not relay the information that I wanted others to receive. I wanted others to understand what people were going through during that time. That is why I decided to use a collage as my mode of art.

- Works Cited

-

“Asian Americans Then and Now.” Asia Society, asiasociety.org/education/asian-americans-then-and-now.

“Chinese Exclusion Act (1882).” Our Documents – Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=47.

“Chinese Immigration to the United States – For Teachers.” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/riseind/chinimms/.

History.com Staff. “Chinese Exclusion Act.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 24 Aug. 2018, www.history.com/topics/immigration/chinese-exclusion-act-1882.

Gibson Nguyen

- Gibson Nguyen's artist statement

-

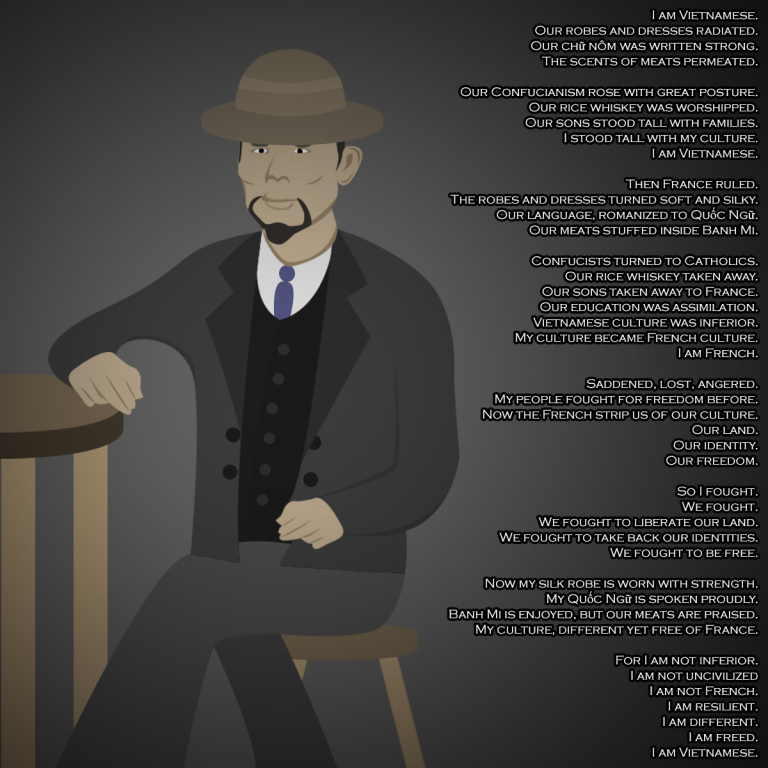

Vietnam has had an interesting history, especially in the twentieth-century. Since the 1940s, French occupation dominated Vietnam and the rest of Indochina. During their occupation, they began to transform the traditional Vietnamese culture, then went with replacing what was already there with French culture. As time went on, Vietnam culture was suffocating whilst French traditions were put into place. Yet as the French continued their subjugation, Vietnamese resistance rose, and by the 1940s, the Vietnamese revolted against their French rulers, leading to the rise of the idea of communism. Today, French ideas and aspects can be seen in Vietnamese culture.

The language, food, clothing, and other aspects of Vietnam have bits of French influence. Yet Vietnamese traditions still remain and are stronger than ever. What made this topic interesting to me was that I didn’t know much about Vietnamese culture before French rule. What I wanted to do was explore more about how French rule influenced aspects of Vietnamese culture, and what fragments of French culture still remained after the 1940s. I was curious to see if I had consumed any cultural products in Vietnam that were heavily influenced by France. This topic is very important to me because I want to learn more about my own culture. My main objective was to understand more about how Vietnamese culture was shaped by its history of foreign rule. During my previous studies on French Indochina, I never showed sympathy or empathy towards this part of world history. I was never given the opportunity to explore more about French occupation. Now I had the chance to look more into what France did in Vietnam, and what came out of their rule. For the mode of art that I did, I wanted to do a poem and a portrait of a Vietnamese man in a suit. The poem would sort of be the story of Vietnamese culture’s transformations from pre-French rule to post-French rule. The poem will illustrate the aspects of Vietnamese culture, how France changed those aspects, and how these aspects were valued before, after, and now. The portrait of the Vietnamese man in a suit would complement the poem by illustrating my interpretation of how the indigenous Vietnamese people felt when France came in and displaced their traditions and ideas. The portrait is to symbolize what the French sought after: the conversion of Vietnamese people to French subordinates.

- Works Cited

-

Burlette, Julia Alayne Grenier, “French influence overseas: the rise and fall of colonial Indochina” (2007). LSU Master’s Theses. 1327.

Giddins, Samuel E. “A Case Study In Imperialism: France in Indochina.” Samuel E. Giddins’ Blog , 26 Dec. 2012, blog.segiddins.me/2012/12/26/a-case-study-in-imperialism-france-in-indochina/.

Pike, Matthew. “11 Ways France Influenced Vietnamese Culture.” Culture Trip , The Culture Trip, 8 Dec. 2017, theculturetrip.com/asia/vietnam/articles/11-ways-france-influenced-vietnamese-culture/.

Jackie Hong

- Jackie Hong's artist statement

-

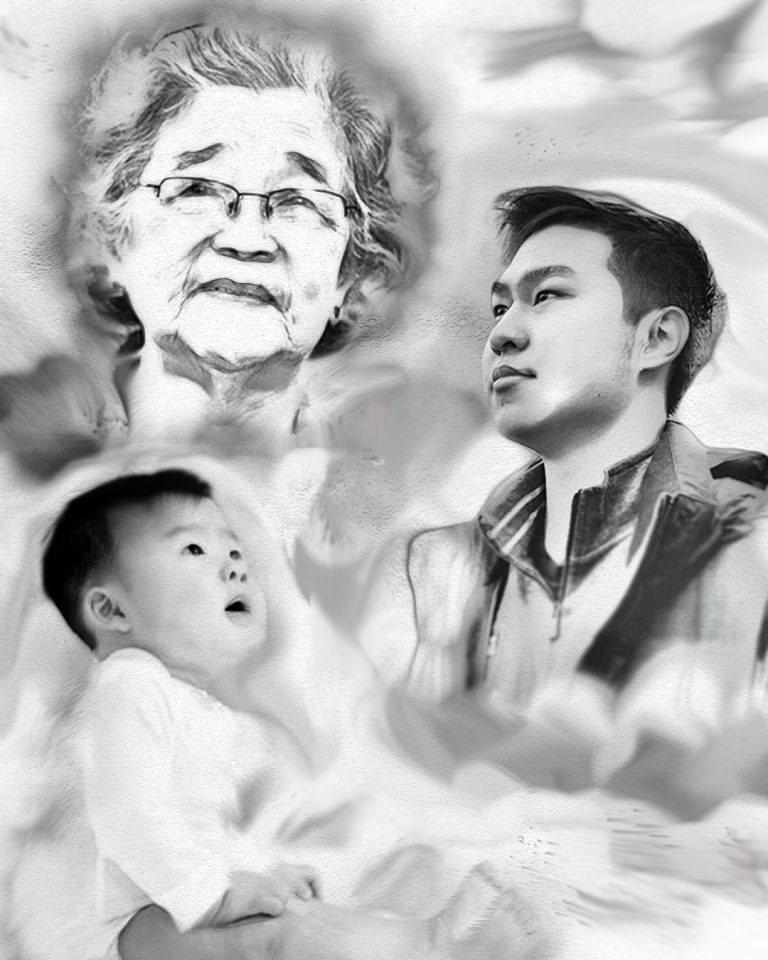

The topic of Asian American generations is interesting to me because every generation after the first has different values, priorities and issues that affect and motivate them. Each generation has distinct reasons for why they are so different from each other and it reflects when talking to a member of their generation. Particularly, I found that the first three generations most clearly show these differences. For first Generation Asian Americans, they are usually immigrants who came to the United States by choice. Some of the challenges they face are language barriers, culture shock, racial discrimination, and the challenge of starting a new life. For the most part, this generation does not have a huge problem regarding their identity because they identify as an immigrant and a foreigner to the country. In the second generation, many of them face new challenges such as their Asian American identity and pressure to succeed in life by their parents while still experiencing racial discrimination.

Their pressure to succeed by their parents provides them with upward socioeconomic movement but comes at the cost of their mental state and social engagement. The third generation can still face identity issues to varying degrees, but the pressure to excel academically and financially is lifted. This may be because the second generation did not have to change their entire way of life like the first and realizing the effects of constantly pushing academics over general wellbeing. This topic is important because people need to acknowledge the generational differences amongst Asian Americans. By understanding these differences, one can be more able to emphasize with Asian American issues and understand where they are coming from. It is personally important to me because I see many of these differences in my parents, myself, and how I would want to raise my own children. Each generation grows up in a different environment and are raised by the previous generation which has a huge influence on their lives and motivations. I chose to make a collage depicting a grandmother, a young adult, and a baby as a way to show three generations of Asian Americans.

Hieu Nguyen Le

- Hieu Nguyen Le's artist statement

-

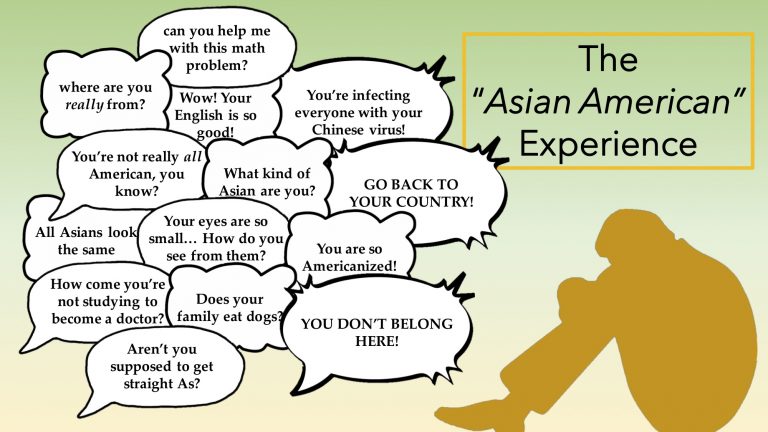

Mental health is a pillar of Asian American identity that succumbs to many unknowns in terms of awareness, attitudes towards mental illnesses, and accessibility to aid. A multitude of factors play a role in an individual’s mental health. For Asian Americans, cultural identity and familial expectation play the largest role in their stress and anxiety that may develop further into depression (Wang, et al, 2011). One aspect that is often overlooked in discussing mental health is the influence of racism.

In light of the discriminatory and racist attacks on Asian Americans due to misconceptions of the coronavirus pandemic, Asian Americans have more to fear beyond the virus itself. The community experienced anti-Asian sentiments and violence over the course of the past few months, from being shouted at to “go back to China” to being stabbed to death (Vang, 2020). Racial discrimination takes a toll on one’s mental being and it drives racial disparities in mental health that negatively impacts the Asian American community as a whole.Racism is not new to the Asian American community, but there has been less discussion about how it impacts individual Asian Americans compared to other racial groups. In particular, every day microaggressions expectations, and other racism-related stress contribute to how Asian Americans perceive themselves and their actions (Wing Sue, et al, 2007). Held at such high standards, Asian Americans are labeled as the “model minority” since they are all hard-working and successful on their own, leading to the misconception that they do not require any attention or help and masking underlying mental illnesses and stresses (Wang, et al, 2011). Asian Americans are less likely to seek out aid for their mental health, and likewise, medical professionals are less likely to advocate therapy and medication to their Asian American patients. Racism-related stress contributes to increased anxiety, low self-esteem, depression in Asian Americans due to emotional and psychological exertion to combat discrimination on a daily basis (Miller, et al, 2011).

For my piece of art, I wanted to depict how verbal racist remarks affects one Asian American’s mental well-being. No matter how minor or severe the comment may be, they all influence one’s mental and emotional being. The minor comments reflect a few of the common microaggressions expressed to Asian Americans, while the few severe comments reflect the anti-Asian sentiments as a result of fear within the pandemic. The comments overlap each other and overbear the ambiguous individual who appears broken to accentuate how racism negatively influences mental health.

- References

-

Miller, M.J., Yang, M., Farrell, J.A., & Lin, L. (2011). Racial and Cultural Factors Affecting the Mental Health of Asian Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(4), 489-497

Vang, S. 2020. US Government Should Better Combat Anti-Asian Racism. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/17/us-government-should-better-combat-anti-asian-racism#

Wang, J., Siy, J.O., & Cheryan, S. (2011). Racial Discrimination and Mental Health Among Asian American Youth.

Wing Sue, D., Bucceri, J., Lin, A.I., Nadal, K.L., & Torino, G.C. (2007). Racial Microaggression and the Asian American Experience. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,13(1), 72-81.

Michelle Simon

- Michelle Simon's artist statement

-

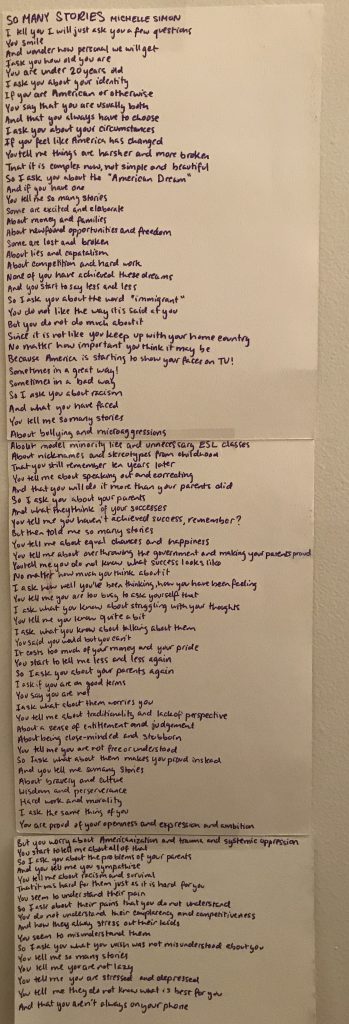

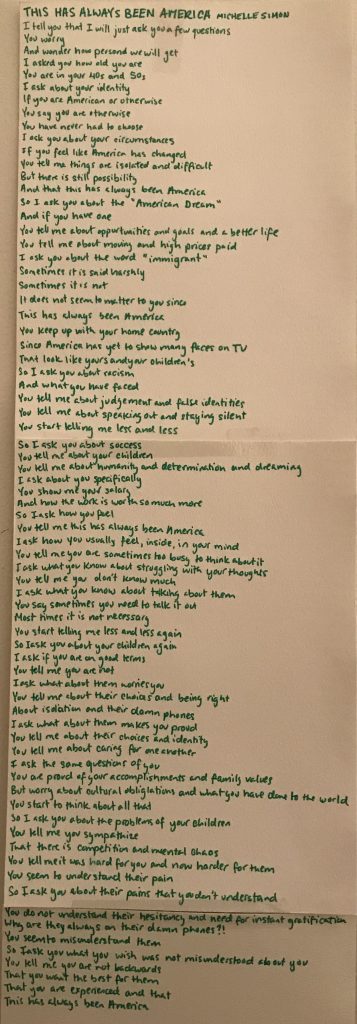

I have thought a lot about the disconnect between my parents’ generation and my own. There is a definite misunderstanding between Generation X and Generation Z Asian Americans that, I believe, fueled the animosity between us. In class we tended to bring our discussions back to this idea. From our conversations, we realized how much the “survival” instinct, a byproduct of immigration, was embedded into our parents. My generation may have grown up in their households, but we are taught to have American dreams based on a “thriving” instinct. I was curious to see how much these instincts conflict with one another, which is why I chose to research the difference between Generation X and Generation Z Asian American’s idea of the “American Dream”.

I have talked about battling biases before, and how I firmly believe it must be done with compassion and understanding and a willingness see the other perspective. While the world is falling into Generation Z’s hands as we become adults, I do not think we should ignore the conflict between us and our parents. Personally, I may be an adult, but I still need my mother. There is a child in me that has never been an adult before and wants to hold my mother’s hand. I do not think I am alone in that parental affection, so I think exploring what has caused the great divide between us is important for our generational healing and personal growth.My goal was to research how the two generations felt about America and each other, and express those sentiments in a free-verse poem. I chose free-verse poetry to give myself as much freedom as possible in expressing the sentiments I researched and creating my own stylistic choices. I created two surveys, one asking Generation X Asian Americans questions about American culture, the other asking the same questions, but of Generation Z Asian Americans. From the results I fashioned a poem and made certain choices in repetition.

The two poems generally follow the same format of the surveyor, who represents myself, asking the surveyee, representing the generation, questions from the survey. What differs is what is answered and repeated. In the Generation X poem titled This Has Always Been America, the title phrase is repeated in the poem whenever the survey answers I received took on that tired tone. In the Generation Z poem titled So Many Stories, the title phrase is repeated whenever the answers took on that excited, dreamer-like tone. I wanted to express how those two tones, no matter how much they seem to contradict each other, do have moments of empathy and agreement. I believe it is those moments that should be capitalized on, so both generations can have a better comprehension of one another. We will, after all, always be their children and they will always be our parents. We should try to understand each other.

Nikitha Gadangi

-

Nikitha Gadangi's artist statement

-

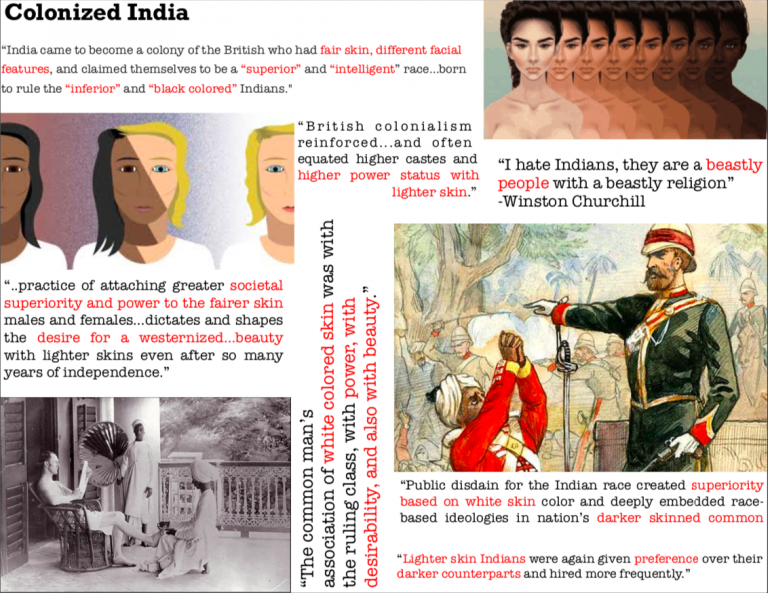

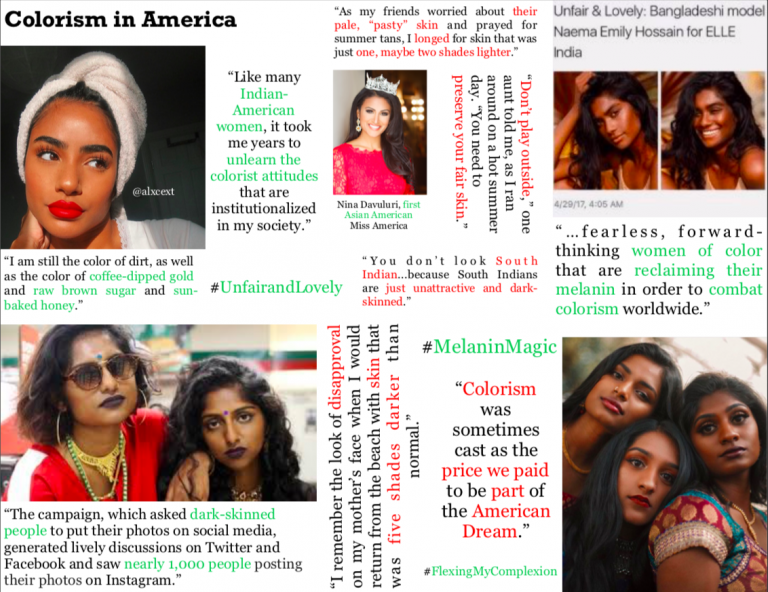

I chose the topic of colorism in South Asia because as an Asian American I have experienced this struggle and feel passionately towards it. Colorism, in Indian culture specifically, is the ideal that those with fairer skin are more beautiful and desirable than those with darker skin. In India, the northern part is generally lighter skinned than those from the southern part. I myself am South Indian so this topic has directly impacted me. Since I was a kid, I have heard remarks like: try to stay inside during the summer, don’t tan too much, stay in the shade if you can, you look black now, why don’t you try to preserve your light skin. As I grew up I realized my older relatives were perpetuating colorist beliefs without even knowing it. It is so deeply engraved in Indian culture that those who are dark should limit or change how dark they are because it is not perceived as desirable. How a culture can hate a whole section of their own range of skin colors perplexed me, as I didn’t think you could possibly change it. But that’s where India’s skin lightening market comes into play, and shows how deep colorism runs through the country and culture.

There is a whole market for skin bleaching and lightening remedies in hopes to turn dark skin lighter by a couple shades. Colorism not only is a mentality, but a way to make money in India.This topic is important because even though here in America the problem is not as severe as in India, the consequences of such thinking still lie in many Indian Americans today. Many Indian American children will not feel immediately comfortable in their skin for many reasons, but colorism can be a prominent and unfair reason. Being the only Indian kid in elementary school can be rough, but also imagine being the darkest of say 3 Indian kids where you can’t fit in for just being darker than the other Indians. Being ostracized for any reason is unacceptable, but colorism is just another way people try to separate SIMILAR people which in my opinion is a harder pill to swallow. It is important for those with darker skin to accept their own skin color and own it because changing your own perspective can be the hardest at times. With many people owning and celebrating their darker skin colors, times will change and lingering colorist beliefs in Asian America will soon fade. I chose this mode of art because I thought it could show the roots of colorism, Indian colorism, and current colorism in America best in a collage form. I juxtaposed images and quotes to show the mindset of colorism throughout these different lenses. I used red text to highlight the negative quotes and green text to show the progress being made with colorism today.

Ryan Li

- Ryan Li's artist statement

-

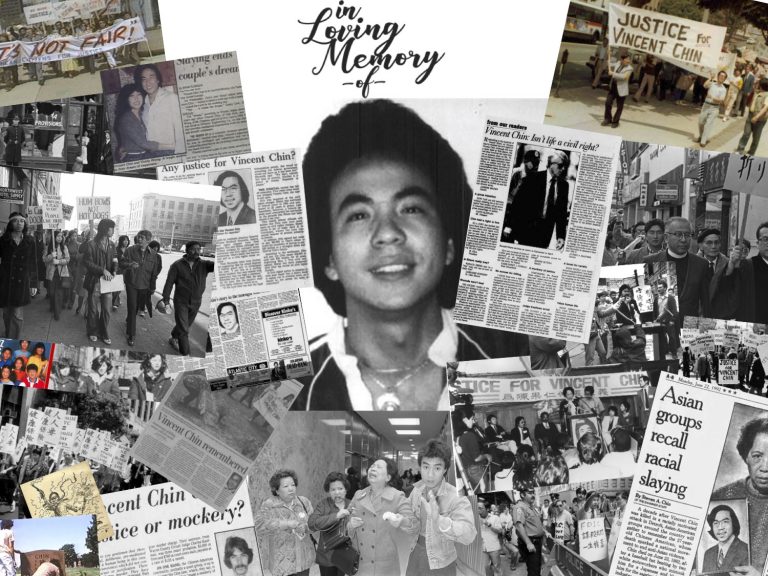

I chose Vincent Chin as my topic because I knew that Vincent Chin was not well known. I watched a documentary called Vincent Who which made me realize just how many people don’t know about the Asian American struggle. Numerous interviews were conducted in which people asked Asian Americans about Vincent Chin. Out of the 80+ interviewees, none of them knew about Vincent Chin. I chose to make a collage to show how serious Vincent Chin’s life was, not just to Asian Americans to America. I have shown newspaper articles, photos of protests, and the effect Vincent Chin has on society. Vincent Chin has been forgotten for so long. Even today, the reverberations of his death are still present in society. Asian Americans are still going through a lot of racism.

Vincent Chin born on May 18th in 1955. However, when he was 27 years old, he got engaged. On June 19, 1982, he celebrated his upcoming wedding by going to a bachelor party. However, Ronald Ebens, a Chrysler Automobiles plant supervisor and Michael Nitz, a laid off autoworker met Chin in a strip club, and assumed he was of Japanese descent. Because of this, they decided to throw racial slurs at him blaming him for the decreased sales in the American auto industry. Whilst verbally attacking Vincent, they also attacked him with a baseball bat. Chin died on June 23, 1982, 4 days later. This is a serious problem. As shown in my collage, there were numerous newspaper titles discussing Asian Americans fighting for the punishment for the two men to be less lenient. However, today, in 2020, I feel that not enough people know Vincent’s story or the struggles Asian Americans have been through in the late 90s. I feel that by presenting Vincent Chin as my project, I will be able to shed some light on the history of past Asian American struggles. Vincent Chin is a quintessential part of the Asian American fight for freedom that started in the 1800s. People always think of the Yellow Peril or the Asian Americans that struggled to create the Transcontinental Railroad. It is an ongoing struggle, in the 90s, there was not enough news coverage on Asian Americans. However, my presentation shows just how much Asian Americans fought in the past. I carefully handpicked newspapers and photos that relate to the Asian American struggle. I made it a memorial to show how this is something we can’t undo. Vincent Chin’s life can’t be returned. He was a victim of racism, and we cannot forget him. By forgetting Vincent and his death, we are devaluing the justice we deserve. We should still be fighting for equality, not just for Vincent, but for ourselves, our families, our communities, and everyone we know. If we forget Vincent Chin, we forget about all the progress we tried to make in the past. We must acknowledge Vincent Chin and how America still oppresses minority races, not just asians but others too. In today’s political climate it is quintessential that we continue fighting for equality. Vincent Chin’s death cannot be in vain. We must all take action to teach others about his death and know that we still have a long way to go before we can be equal.

I chose to make a collage because it was an efficient way of portraying Vincent Chin and his life. I found photos of protests and Asian Americans fighting racism. I also showed news articles showing the bias towards the two white men. In these news articles and photos, one can see that the 90s were not a quiet time for Asian Americans. Asian Americans have been fighting for their freedom and equality for so long. My collage serves another purpose in which it shows an explosion of Asian American interaction with the media. It essentially shows an “explosion” of history people would never know by themselves. A typical person, Asian American or not, may not look up the history of Asian American struggles, however, this collage essentially showcases the numerous times we Asian Americans have fought for our rights. My collage also serves as a memoriam for Vincent Chin, with Vincent being the focal point of the entire poster. A collage is the best way to commemorate someone. It can showcase their life and their struggles, their successes, flaws, and strengths. In this case, I showed photos and images of newspapers and protests to show the history of the Asian American fight for history. I have shown the earliest political cartoons from the 1800s up to the late 90s protests. Vincent Chin encapsulates all of this.

- Works Cited

-

ColorLine. “Remembering Vincent Chin.” Remembering Vincent Chin – The Color Line, TheSocietyPages, 28 May 2015, thesocietypages.org/colorline/2012/06/19/remembering-vincent-chin/.

“Film Screening for ‘Who Killed Vincent Chin?,’ March 8.” Sampan.org, SampanSyndicate, 5 Mar. 2020, sampan.org/2020/03/film-screening-for-who-killed-vincent-chin-march-8/.

Fish, Eric. “35 Years After Vincent Chin’s Murder, How Has America Changed?” Asia Society, 16 June 2017, asiasociety.org/blog/asia/35-years-after-vincent-chins-murder-how-has-america-changed.

JACLFoundation. “Asian American History.” Japanese American Citizens League, Japanese American Citizens League, 8 Mar. 2014, jacl.org/asian-american-history/.

Lam, Tony. “Vincent Who?” YouTube, Asian Pacific Americans for Progress, 9 Apr. 2009, www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL3F74C2EF67CCECD1&disable_polymer=1.

Mei, Mary. “The Model Minority Myth Reborn in the 1980s.” Development of Asian American Higher Education, Darthmouth, 2019, www.dartmouth.edu/~hist32/History/S25%20-%20Model%20Minority%20Myth.htm.

Sang, Elliot. “It’s Impossible to See Racism Toward Asian Americans Right Now and Not Think of Vincent Chin.” Medium, GEN, 30 Mar. 2020, gen.medium.com/its-impossible-to-see-racism-toward-asian-americans-right-now-and-not-think-of-vincent-chin-47def703b2dd.

Society, Asia. “Asian Americans Then and Now.” Asia Society, Center for Global Education, 14 June 2016, asiasociety.org/education/asian-americans-then-and-now.

Wang, Frances Kai-Hwa. “Who Is Vincent Chin? The History and Relevance of a 1982 Killing.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 15 June 2017, www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/who-vincent-chin-history-relevance-1982-killing-n771291.

Wang, Frances Kai-Hwa. “Who Is Vincent Chin? The History and Relevance of a 1982 Killing.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 15 June 2017, www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/who-vincent-chin-history-relevance-1982-killing-n771291.

Wikepedia. “Murder of Vincent Chin.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Apr. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_Vincent_Chin.

Wu, Frank H. “Why Vincent Chin Matters.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 June 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/06/23/opinion/why-vincent-chin-matters.html.

Yu, Heather Johnson. “35 Years Ago, Vincent Chin Was Murdered in Cold Blood For Being Asian.” NextShark, NextShark Corporations, 24 June 2017, nextshark.com/vincent-chin-murder-35-years-ago-2017/.

Samantha Quan

- Samantha Quan's artist statement

-

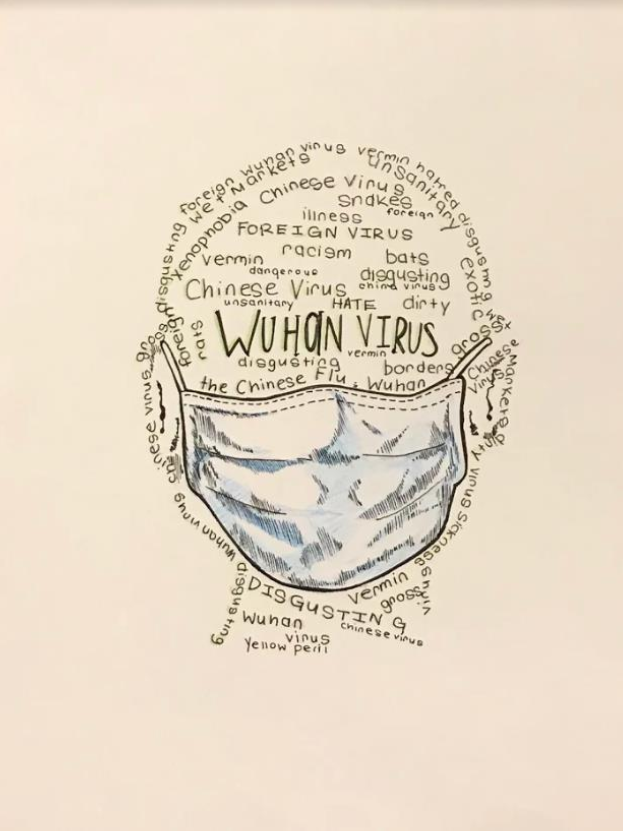

I chose this topic to focus on because it is relevant to the Asian American experience during the pandemic. In the past few months, news sources and President Trump have been referring to the COVID-19 virus as “Wuhan Virus”, “Chinese Virus” and “China Virus”, this nomenclature can and is endangering Asian Americans. According to Vox, “racializing pandemics by attaching them to a specific place and people, othering a pathogen that originated in another land in much the same way white Americans have historically othered people of color who came to (or whose ancestors came to) the United States from somewhere else.” (Vox). This “othering” opens doors for violence and hate towards the Asian American population in the United States. It is important to address because Asian American lives are endangered.

Recently in the news, an Asian American was attacked at a Sam’s Club in Texas. The perpetrator was accused of attempting to murder three Asian American family members including a toddler and a six year old child. The suspect indicated that he stabbed the family because he thought they were Chinese and spreading the coronavirus. This association with Chinese/Asian people and the virus is built from blatant racism and ignorance, it is in keeping with disease drawing out of the fear of foreigners. Furthermore, it enables stigma of Asian people and builds a perception that all Asian people are disgusting and eat bats and snakes. I chose this mode of art to symbolically represent what Asian Americans are feeling in the pandemic crisis. The words (that form a shadow of a person) are being seen in the news and are used to attack Asians. The image is suppose to represent how these words are being misused to represent Asians and how they are affecting Asians. It also represents how people are not seeing Asians as human beings but exclusively carriers of the virus solely based on their race.

- Works Cited

-

Miguel, Ken. “Here’s the Origin of Coronavirus or COVID-19 and Why You Really Shouldn’t Call It That Other Name.” ABC7 SanFrancisco, 3 Apr. 2020, abc7news.com/how-did-coronavirus-get-its-name-of-for-new/6071514/.

Scott, Dylan. “Trump’s New Fixation on Using a Racist Name for the Coronavirus Is Dangerous.” Vox, Vox, 18 Mar. 2020, www.vox.com/2020/3/18/21185478/coronavirus-usa-trump-chinese-virus.

Spinney, Laura. “It Takes a Whole World to Create a New Virus, Not Just China | Laura Spinney.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 25 Mar. 2020, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/25/new-virus-china-covid-19-food-markets.

Stephanie Wang

- Stephanie Wang's artist statement

-

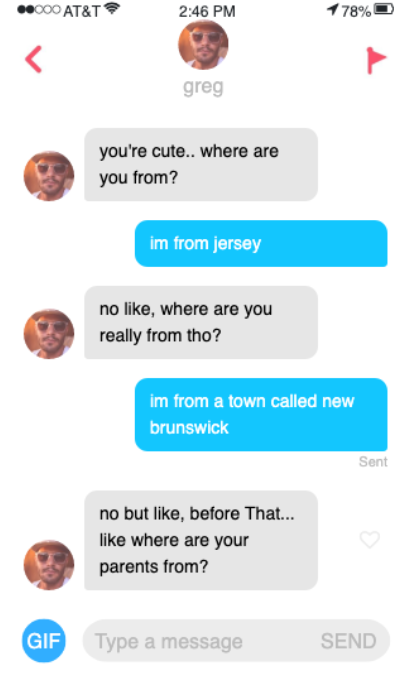

The reason I chose this topic is because it’s highly significant and is something that is still on-going. The phrase “Where are you really from?” or even various forms of it are an act of racial microaggressions that disseminates the idea that Asian Americans are and will continue to be perpetuated as foreigners. A “microaggression,” is defined by Merriam Webster as “a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group”. So essentially when this phrase is repeated by someone, they are insinuating that no matter how long we’ve been in the U.S., or if we were born here and English is our native language, they correlate our facial features and the way we look, to our racial or ethnic backgrounds.

This is important because it’s critical to highlight that just because we are of Asian descent, we are not any less American. The question seems harmless and is often asked with no clear ill intent, but it usually depends on who is asking and the context it is being used in. Sometimes when we don’t give people the answer they want; they make an effort to start a “let me see how many tries it takes to guess your ethnicity right” game. This issue is not only relevant in the Asian community, but in essentially any community that is not White. All Americans should be able to feel equally American. No one should have to defend their own nationality in their own country. Being on the receiving end is very off-putting and makes us question our belonging.But, the truth of the matter is, most people don’t really care about where we’re from, they just want to be able to put us into a box and talk with us about our lives as if it’s something they can relate to. The reason I chose to make my art a Tinder chat was to symbolize all platforms of social media. Though many of these types of questions are still asked in person today, a lot of it has moved online to social media and dating apps.

Vi Rong

Project not shown

- Vi Rong's artist statement

-

I chose to explore the significance of names in constructing one’s Asian American identity as this final project’s Asian-American related topic and issue. For my project, I interviewed several college-aged individuals of Asian-American descent with questions concerning their name and its meaning and significance. I gathered information on their cultural background, naming traditions, the struggles they faced with regards to their name, how they approached and reacted to mistakes, and general thoughts pertaining to the Asian-American experience in the States. Using an array of individuals from differing backgrounds highlights the fact that the Asian population is not a monolith. Each person has their own unique experiences with the names and culture they associate with.

A video was made out of the audio recordings from the interviews. To preserve their privacy, their faces are not shown, so the art form could be considered more of a podcast. This mode of art presents the personal stories of individuals in an authentic manner: their ideas and thoughts are expressed using their own words and feelings. The video is an accessible medium and makes it easier to relate to the stories, as the audience is able to focus on listening directly to the speakers. Most importantly, with this audiovisual format, the interviewees are able to pronounce their names the way they are meant to be pronounced.. A name can be more than just a word; it can reflect one’s gender identity, pay homage or express gratitude to loved ones, define familial ties and associations, and overall represent one’s family and culture. When one’s name is not respected or treated with the proper care, it is disrespectful, alienating, and dehumanizing to the person, denying them their right to decency and identity. For those with non-American names, they often struggle with mispronunciations, misspellings, jokes made out of their name, and other mistakes or disrespectful acts. These names can even hold people back from social mobility and equal treatment in their social and work lives (Park, 2019; Pinsker, 2019). Racial minorities may use their name to reflect their ethnic and racial identities, which are real, ascribed aspects of identity that can have social and political consequences (Akiyama, 2008). Because they are non-white Americans, people of color find that they must shoulder the burden of adjusting the way they live and identify as a result of having nonconventional American names (Park, 2019). They face discrimination, racism, and xenophobia over their name. This topic is important as it is a reminder to be critical of why certain names are preserved, namely those with European-roots, while non-white names are expected to change in order to assimilate or accommodate societal norms.